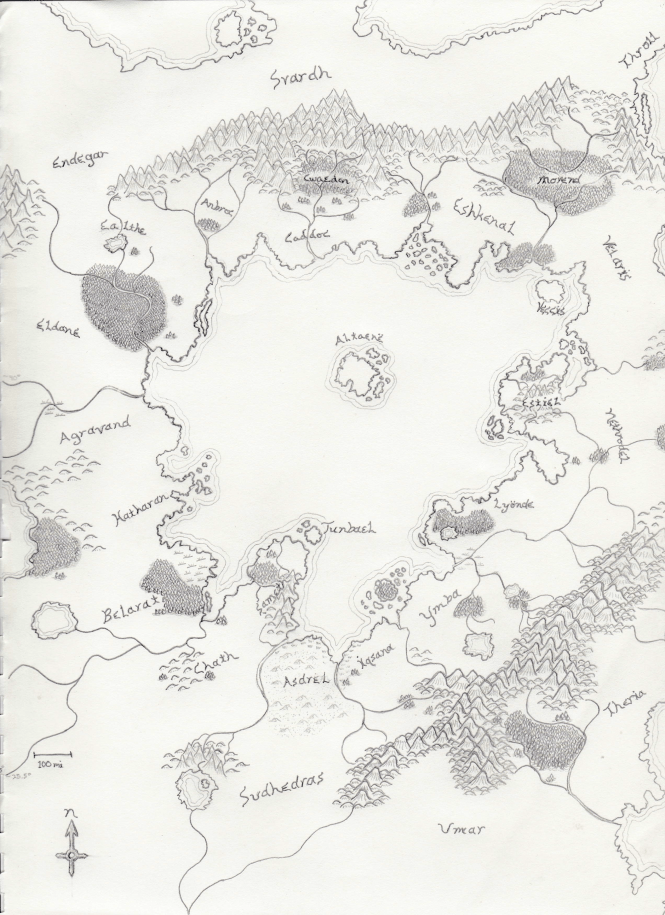

Every aspiring fantasy author or worldbuilder must eventually answer the question of what kind of sentient beings will populate his or her world. At that juncture (again) myself, I thought I’d write my way through the problem(s). I’ve agonized over and over again in designing Avar Narn about what “races” (they should really be called “species,” I think) would occupy that world. I’ve made changes and undone them, remade them and tweaked them over and over and (I hope) I’m ready to finally make the decision once and for all. We’ll see at the end of this post.

So what are the problems about “race” in fantasy works?

(1) Ideas of race have meaning and are problematic. Since you’re on the internet to read this, I’m going to assume that you’re aware of how big a deal race currently is in our world (and in the U.S. in particular). How we discuss and think about race is important, and it’s quite easy to make a misstep.

From one perspective, having various races (I’m just gonna say species from now on) in your fantasy world can do a lot for you.

First, the genre is called “fantasy”—readers want to see the fantastic. It’s part of the fun. Second, you have an instant source of potential conflict (and therefore plot) when you have groups of people (in this case fantastic species) who are unlike one another.

If we want to be highbrow, the encounters between different species allow us to look at “otherness” (to borrow the academic term) in a lot of interesting ways—we can analyze and critique how we (by our culture, our ideologies or our very humanity) define and react to the Other. We can, if we want to be heavy-handed, even talk about specific races race-relation issues in the real world through the metaphor of created fantastic species. To be honest, I’m not sure how you could portray enslavement in a written work and not have an American reader not think about the historical slavery of blacks, and the line between what is said about slavery in general and what is a specific commentary on the experience of a particular people is blurry at best.

At the same time, when we create a fantasy species, we have to bring them to life and individuate them. It’s no use saying “these people are like humans, but they’re blue and have an extra eye.” If our differences are only cosmetic, readers will be understandably disappointed in the lost opportunity. But defining peoples and cultures is difficult, and it’s tempting to resort to shorthand: “These guys are like Tolkien’s orcs, but they’re more intelligence and have a culture like ancient Egypt.” Time constraints and a desire to give the reader quick access to understanding of a story push us in this direction. But there’s a trap here—this sort of cribbing can easily drive us to base our fantastic species off of racial stereotypes.

Even Tolkien was guilty of this. He later acknowledged without reservation that the dwarves in his stories had a lot in common with European Jews. Re-read the stories (or re-watch the movies) and think about that—Tolkien’s dwarves have big noses, are geographically displaced, are often greedy and selfish. If the dwarves weren’t such beloved characters, we’d really see some elements of anti-Semitism here. I’m not saying that Tolkien was anti-Semitic; I have no idea about the answer there. But if it’s possible to say that his portrayal of the dwarves perpetuated negative Jewish stereotypes (mostly medieval ones that somehow persist in this case), something negative has been accomplished through writing, and that’s to be avoided.

(2) Clichés. Look at some of the most popular works of current fantasy fiction (A Song of Ice and Fire and The Name of the Wind both come to mind) and you’ll see settings in which you will not find elves and dwarves and Hobbits. There are several reasons for this.

If you want to have fantastic species in a setting or story, ask yourself, “why?” really. Can you tell the same type of story (or even the exact same story) with humans instead of different species? In most cases, the answer is “yes.” If there’s an Occam’s Razor of writing, maybe this is where it best fits—don’t put things in the story you don’t need. That advice sounds really good, but that doesn’t mean I can bring myself to follow it, necessarily. Sometimes there are things I want a story to have.

The more important reason, I think, that there’s a current move away from fantastic species in modern fantasy, or at least the “standard” species (elves, dwarves, halflings, etc.) is that the portrayals of these species has become hackneyed. We’ve had the same pointy-eared elves and pseudo-Norse dwarves for seventy years and, after a while, that starts to lose its fantastic luster.

This is partially a result of Tolkien’s looming presence over the genre—if you’re not doing it like him you’re not doing it right—but it’s also a result of the influence of Dungeons and Dragons. Multiple generations of fans of fantasy have grown up with the roleplaying game’s definition of elves and dwarves (influenced, of course, by Tolkien) setting the standard. We writers now must worry that, if we change the stereotype, readers will say, “that’s not what orcs are like!” while established writers (and many readers) also say, “if you’re using the same old stereotypes, you’re not writing something worthwhile.” I don’t think that the latter statement is necessarily true, but the risk of writing overly-derivative works certainly increases with the use of the “stock” fantasy species. As an aside on that note, perhaps we could argue that the “stock” species should be thought of in the same line as Commedia dell’Arte: as stereotypes that allow us to quickly pull in the reader and get on with the story. After all, avoiding an infodump is usually a good thing.

To be clear, there are modern writers doing wonderful things with (at least mostly) traditional stereotypes. The books of The Witcher world contain elves and dwarves but manage to depict them in a believable and relatable conflict with humanity (that disturbingly resembles a race-war, because it is one). Of course this works especially well for Sapkowski in the larger context of taking traditional fairy tales and twisting them for his own purposes.

(3) It’s impossible to get inside the head of ultimately alien creatures. As humans, we simply cannot fathom what it would be to be a thousand-year-old elf with confidence in her immortality. How differently we would view the world.

To be fair, that’s a surmountable obstacle. We also cannot create a character who is actually every bit as complex and idiosyncratic as a real person. But we can create the illusion of the same. The same principle applies to writing about fantasy species (or alternatively, alien cultures in sci-fi settings)—we can create the illusion of unfathomable otherness.

Though crafting the illusion is possible, it’s nevertheless very difficult. It requires great care and thought to do well, otherwise you end up with phenotypically-variant humans and nothing more.

It’s not enough to give them a culture based on human cultures, I think. If you’re going to create species that really deserve to be something other than humans, they should really feel different, probably even uncomfortable (but not necessarily frightening).

(4) Complicated Relationships. I grew up a big fan of the Shadowrun setting. One of the things that bugged me about it though, is how they treated race. By this, I don’t mean the fact that there were Orks and Trolls and Elves and Dwarves, but about the ethnic differences we tend to mean when we use the word “race” in modern context. The Shadowrun rationale was just too simplistic.

The explanation went something like this: “Twentieth-century racism is a thing of the past. People don’t care about someone’s skin color anymore when the troll over there can crush you with his bare hands.” In other words, the existence of the alternative species of the Shadowrun world had completely subsumed “traditional” racism.

There’s no reason to believe that that would be the case even if people in our world were to suddenly turn into elves and such. There’d still be plenty of “good ol’ fashioned racism” to go round.

This is just an example of a problem that’s really inherent to all fantasy writing–the need to balance complexity with both the writer’s time and energy and the importance to the story.

(5) Monocultures. This relates closely to (4). Humans have a diversity of very different cultures, ideologies and values, but fantasy species tend to be portrayed as monolithic. This practice is most prevalent, at least in my experience, in roleplaying games. A setting may have many different human cultures for players to choose from for their characters, but only one for any character of a non-human species. Sometimes there are two or three options, but these are not terribly fleshed out and are based more on in-game bonuses than real cultural differences. The ad absurdum example, of course, is early D&D, where you could have either a class (magic user, thief, fighting man) or a “race” (like elf). That’s right, all elves are so similar that they need only the name of their species to define their abilities.

The point is, believable species must have individuation between groups and between individuals. If you’re using elves in your fantasy world, they shouldn’t all be flower-loving hippies (or, even more offensive, all be evil if they happen to have black skin). It takes extra time, yes, but if you’re going to be using fantastic species in your writing, they ought to be diverse like humans are diverse (or there had better be a good reason why they have a monolithic culture).

(Potential) Solutions

(1) Avoid the subject altogether. Just don’t use fantastic sentient creatures. Throw in all the griffons and gargoyles and what not that you want, but leave the thinking, feeling characters human.

(2) Cheat. Here’s what I mean: in Avar Narn, several of the fantastic species used to be human—they were reformed, accidentally or on purpose, willingly or not, by magic. That’s happened long ago enough that they’ve developed somewhat alien perspectives on existence and certainly cultures that vary from those of most human cultures, but it leaves within them a core of humanity that somewhat eases the problem of creating an entirely alien culture—humans will definitely be able to relate to these beings on some level, but not completely. One of the reasons that I’ve chosen this path for some (but not all) of the fantastic species in Avar Narn is that it reinforces one of the setting’s themes—the horrible things that humans would do to themselves if given the power to reshape the world through magic.

(3) Be defiant. Just say, “Damn the torpedoes; full speed ahead!” and use the traditional fantasy “races” in your stories or setting. If you write those peoples in a believable and interesting way, and especially if the other aspects of your stories are well done, you won’t have to worry about most people complaining. Ignore the ones who complain anyway.

(4) Use alternate mythologies. Tolkien was a philologist, a student of (ancient) languages. He had spent a long time studying Old English and Old Norse, and he drew from Germanic mythology to create his elves and dwarves. But there are many other cultural mythologies from which could be drawn a plethora of new and interesting species to populate your fantasy world. There are plenty of authors, published and not, taking this tack, though, so move quick (this is what Miéville did in Perdido Street Station and the books that follow, for instance).

(5) Use Archetypes. Here I mean Jungian or Campbellian archetypes. I’m not sure that I buy into the whole “monomyth” thing, and I’m a little skeptical about there being a collective unconscious from which we separately derive the same concepts (fascinating as that idea is—especially for fantasy writers). But there are some very common “places” occupied in various mythologies around the world—there are “hidden folk” in both Scandinavia and Southeast Asian countries, smith creatures in all manner of cultures, creatures to be sought for wisdom in many mythologies. So, find those common themes and, instead of drawing upon an existing mythology to find your fantastic species, create your own that fits the motif. Both dwarves and giants are associated with smithing in various European cultures, so what other type of creature might fit there?

(6) Do the twist. Take a traditional fantasy race and tweak it until it’s either an interesting and innovative take on the species or no longer resembles the original concept.

(7) Use biology. Look to how organisms develop and change based on environment and use that to create your fantastic creatures. There’s a caveat here, though—you’re creating a world that readers will be willing to suspend disbelief for, not an alternative science textbook (unless, of course, that’s your postmodern, avant garde sort of writing style), so use what you need and maintain plausibility to the extent you can, but don’t worry too much about having things perfect. And avoid the math. For the love of God, avoid the math.

(8) Create from scratch. This is not “create ex nihilo,” which humans are incapable of doing. But, if you take your building blocks from less-visited wells, you can create something that feels different and unique.

(9) Relax. At the end of the day, the important question is not whether you include or exclude elves in your fantasy—it’s whether you craft a world that seems to make sense (that is at least internally consistent and plausible-seeming based on human experience), craft species and characters that are entertaining and interesting to read about, and tell stories that draw the reader in and make him not want to finish. Can you do that with stories that include elves? Yes. Can you do it with stories that have unique fantasy species? Of course. Could you do either badly, absolutely. So suck it up, figure out what you want to have in your world, do your homework to create diverse and interesting inhabitants for your setting, and get writing.

Have I made my own decisions now? Not exactly, but at least I’ve given myself the kick in the pants I needed to make my final decisions and let it ride.