(So I’ve been promising for some time that I’d post some short stories set in Avar Narn on the blog. Well, I’ve been slow in the writing and even slower in the editing of those more “official” stories and they’re still likely a short ways off. So, in the meantime, I’ve decided to publish the short short story below, written rough and mostly to shake the dust off, edited only slightly, and on the lighter/sillier side of things. )

(You can read this short story in PDF here: JM Flint – Avar Narn – Kenning)

“Tardarse? Why do they call him that?” Hrogar asked.

Ranald grinned. “We took on Vix when he was just a lad. His parents had fallen on hard times and we got him cheap—mother needed to keep her forge going or some shite like that. Anyway, he’d done what growing up he’d done learning to pound steel, so he had a fair bit of muscle on his scrawny frame. The boys and I figured we needed a porter and someone to tend the campsite, polish the armor, do all the shite we’d grown tired of, yeah?

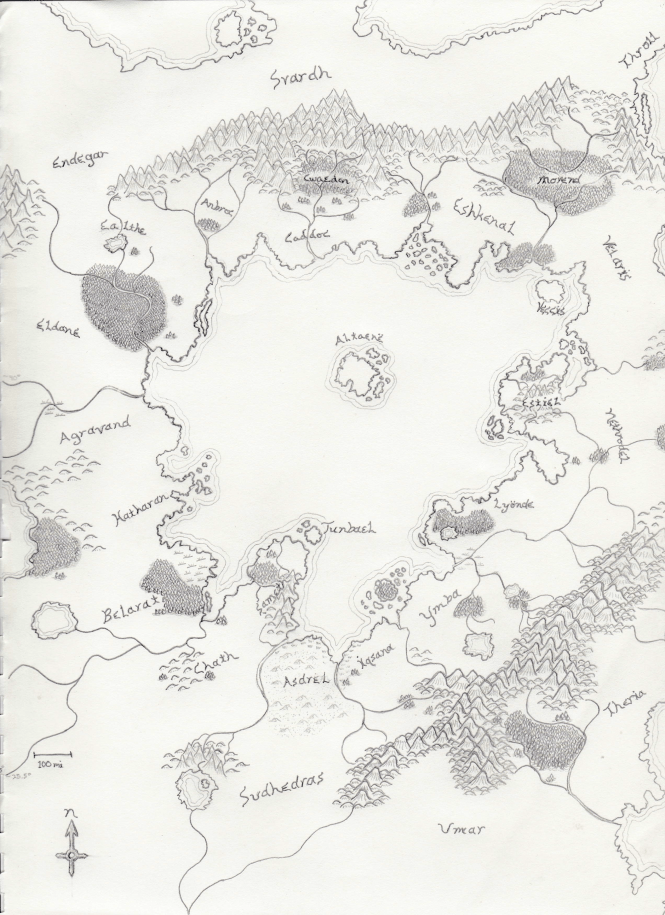

“He’d been with us about a year; must’ve been about fifteen or so, and he’d fallen in just fine with the Ravens. So there we were in the west of Eldane, just about to set out on an expedition for one of the Houses toward some place o’ death and fortune; I forget which.

“It was uncharacteristically hot for the start of the campaigning season, so we hadn’t made it too far trekking that day, loaded down with our baggage train as we were. Exhaustion fell on us all and we stumbled about like shamblers as we made camp. No one talks about what shite adventuring is, a lot of discomfort and boredom punctuated by sudden terror.

“In the small hours of the morning, a facking orcene wanders into the camp, stirred I guess by the warm night air and its own hunger. Filthy facker it was, skin grey and scabrous, hair matted and mottled, coated in a layer of shite and mud, fungus growing in the creases of its gluttonous form like it had been some boulder sitting in one of valleys of the hill-country. Half again as tall as a man, and its dark eyes flashed with hatred for all things civilized and human, hungry to destroy, defile and devour.

“Apparently Marten, who’d been supposed to be on watch at that time, had fallen asleep at his post. Only embers glowed in the fire pit we’d dug and we awoke to the sounds of the monster ripping apart one of our horses with its bare hands. It’s hard to think with the screams of a dying horse filling your ears, but me and the boys have been through worse shite than that and, groggy as we were, it weren’t long before we were unsheathing swords and yelling to each other in our battle-tongue, preparing a concerted counter-attack.

“So I take a peek out of the flap of my tent, and sure enough, there’s the facking thing starting to come into the camp proper, dragging Marten by the foot. Now he’s screaming along with the damned horse and it’s getting harder to hear me mates as we form a strategy. I see our patron look out of his tent. As soon as he sees the orcene he starts facking screaming, too, like he were a little girl and you’d just ripped his dolly from his hands.

“Course, this gets the beast’s attention and it wheels around, leaving Marten and moving towards the patron. I’m just about to call the boys to attack when out facking rushes Vix from his tent, naked as the day he was born, screaming at the top of his lungs. I guess he’d taken his clothes off to sleep in the heat, but he looked like one of the wild folk on a raid into a mountain village, on the warpath to rape and pillage.

“The only thing he’s got in his hands is a wooden practice sword we’d been training him with. Bravest, stupidest thing I ever saw. So now Vix is charging the orcene and it turns to face him with a look of shock and confusion. He brings the waster down on the beast’s knee, breaking the wooden weapon and sending splinters everywhere. I hear some of the boys start laughing, and can’t help but do the same—it’s the strangest thing, this naked boy screaming like some blood-crazed berserker, the monster yelling back in sheer disbelief and the sword-stick still coming up and down like an ax, like Vix is trying to chop down the tree of the monster’s leg. Only it’s not really that funny, because we’re about to watch this boy die.

“The orcene raises its hands to smash Vix, and I’m sure I’m about to watch the boy’s head explode like a jar of jam. But Vix takes the opening and facking swings the fragment of the wooden sword in a rising strike at the creature’s groin. There’s a sickening splunch as the stick connects with the beast’s stones. As one, the men of the Company grunted in sympathy; enemies though we were, no man wishes such a wound on another.

“Like he’s some facking dancer in a mummery, Vix rolls between the thing’s legs before it brings its hands down to its wounded manhood. Now it’s screaming louder than the horses or any of us, doubled over and clutching at itself as you or I would do in its place.

“And Vix, this look of grim determination on his face, like he’s never facking heard of that thing called fear, walks his way back around to the front of the beast while it’s distracted and proceeds to stab the facker in the face with the stub of the wooden sword, spraying blood and ichor across him as he destroys the thing’s eyes.

“The orcene’s unsure whether to protect its manhood or its face, and I swear the thing’s sobbing to itself. Now it’s the one who’s scared, and Vix is going about his business like he’s facking saddling the horses, taking his time and—ask the boys—humming to himself. He walks over to me tent and picks up a spear I’d leaned against a nearby tree. He’s still buck naked, mind you, and he looks up at me, surprised to see a human face. The shock of the recognition drains the calm from him and he starts to shake as his nerves take hold.

“‘Finish it, boy,’ I tell him.

“Still shaking, he readies the spear in both hands and charges the orcene, jumping at the last moment and bearing the spear in a downward arc that pierces the monster’s neck, driving the facker onto its back and pinning it to the Avar. There’s a fountain of blood spews up from the wound and covers the boy, and now he really looks like one of the wild folk all painted up on a raid from the mountains.

“The boys and I come out of the tents hooting and clapping and carrying on like we’d just seen a show in an Altaenin brothel. Apparently, this scares Vix and he lets out a shrill scream as he turns to see us. This scares him after he’s brutally and efficiently skewered a monster that by rights could have given us all a good fight. Now he’s trying to cover his manhood with his hands, like he’s some virginal maid we’ve come upon bathing. He’s got this stupid look on his face like he’s done something wrong and he’s about to get whipped for it.

“Marten wraps an old cloak around him and hands him a mug of ale. ‘Faaaaaack. Stupidest thing I ever saw,’ Marten’s telling him, ‘that thing could’ve smashed you to bits. What in the Abyss drove you to such a thing?’

“‘I—I thought you was all dead,’ Vix stutters. ‘I’s angry is all, I guess.’

“‘Tardarse,’ Greygan says, smiling. ‘But better stupid than good, I ‘spose.’

“And it stuck. We all called him Tardarse from that point on, and he was one of us. Not some porter or servant boy we brought along to ease the hardship of travel, but a man of the Company. A Raven. It wasn’t the last stupidly brave thing I’ve seen him do and survive, neither. There’s good Wyrgeas on that one. Got to be, as much trouble as he gets himself into and finds a way out again.”